This story contains graphic material and references

The following story is upsetting, but it’s part of the reason Sylvia’s CAC is here today. Reader discretion is advised.

How one of the most tragic stories in our state’s history began our mission to protect and care for children of abuse from every corner of our community

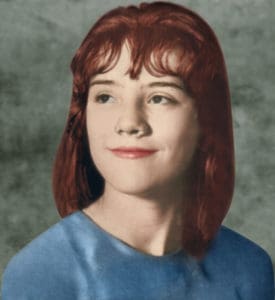

In October 1965, 16-year-old Sylvia Likens died after being held captive for nearly three months. Her death sparked action across police departments, prosecution, and the halls of the Indiana General Assembly, plus movies and books.

Before leaving for a lengthy work-related trip and undergoing immense financial stress, Sylvia’s parents departed Lebanon and left her with a caregiver, Gertrude Baniszewski in Indianapolis. As a teenager, Sylvia babysat, hung out with friends, did chores and small jobs, loved the Beatles, and lived an otherwise typical life.

In the summer of 1965, Sylvia and her sisters moved into Baniszewski’s home at 3850 East New York Street. They continued to live as teenagers do, singing, skating, earning modest incomes during the summer break, and doing housework.

The financial hardship of Sylvia’s father continued, and payments to Baniszewski for boarding began to wane. Angry, Baniszewski began beating the children in the home across their buttocks. By August, the beatings exceeded a dozen a week, often for benign issues like eating too much food.

Soon, Baniszewski was focusing on Sylvia. Later testimony would reveal Sylvia was beaten and abused regularly after school and on weekends. She was deprived of food, and later still resorted to eating food out of garbage cans.

Her sisters and Baniszewski began turning on Sylvia, becoming bitter at her appearance and having claimed to have a boyfriend. She was accused of spreading rumors about Baniszewski, which was unfounded. The boyfriends of her sisters also began to turn on Sylvia.

By the end of the summer, Sylvia was being raped, verbally tormented, assaulted with objects physically and sexually, starved, beaten, burned, and forced to commit humiliating or heinous acts. Baniszewski eventually forbade her from attending school and she was held captive in the home.

Why didn’t anyone do anything?

After a failed escape attempt, and then the eventual death of Sylvia from escalating torture, like burns followed by rubbing salt in wounds, police found “the most sadistic” and “awful crime” they had ever seen.

Neighbors reported to police they sometimes heard her screams, or someone asking for help. But in 1965, no one felt compelled to come forward. The notion being, “It wasn’t their business or place to intrude on someone else’s household.” One neighbor said the screams stopped around 3:30 am on the morning of October 26, 1965. By 6:30 that afternoon, she was dead.

Her teachers and other adults likely noticed the open sores, bruises, or early signs of abuse. They just didn’t feel empowered to say anything.

The tragic legacy of Sylvia Likens

An autopsy revealed over 150 separate strikes against her body. They included burns, muscle damage, nerve damage, a swollen vaginal cavity, fingernails broken backward, and she had reportedly bitten through her lips.

Taken back to Lebanon, she was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery on October 29, 1965.

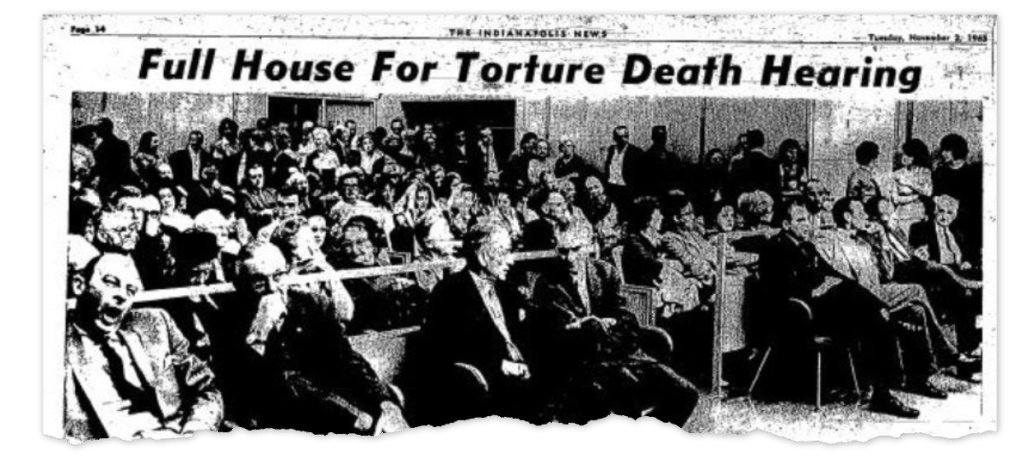

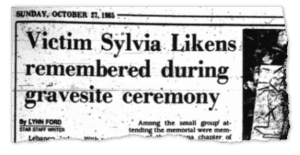

The trial, testimony, and indictments were all jarring to everyone who read about the story. Baniszewski and others were punished and jailed for their crimes. In 1970, the Indiana Supreme Court reversed the convictions because the trial court refused motions for a change of venue and separate trial. A subsequent retrial led to a guilty plea. She was released in 1972, subsequently tried for murder again, and sentenced to life in prison. She changed her name and was paroled in 1985 and died five years later in relative obscurity from lung cancer in 1990.

The uproar of her case, media attention, release, and other crimes led to considerable changes. Sylvia’s case is credited with Indiana’s Mandated Reporter law, requiring everyone in Indiana regardless of age or profession to report any suspicion of child abuse to law enforcement.

Prosecutors and police began to understand the investigation of child abuse and neglect more. Schools and other child-first organizations began to understand more, too, and identify the signs of abuse.

Sylvia’s tragic death shocked an entire state and community into recognizing the horrors of child abuse in a way no case had before or since.

Sylvia’s CAC is named in her honor. We work every day to remember her name, honor her life, and protect children in Boone County from the same anguish and torture Sylvia endured.

Donations support Sylvia’s CAC

Forensic interviews and victim advocacy services are provided at no-cost to families. Transportation, prevention education, office supplies, our lease, utilities, and more are paid for by donations.